Case Study #2 a jetty

Walking along a wooden jetty extending over the water is a pleasant recreational activity. A warning sign displayed at the entry point is reassuring because it warns of risks of injury.

But not all warning signs are effective as risk warnings. The sign examined by the NSW Court of Appeal in Coffs Harbour City Council v Polglase [2020] NSWCA 265 (23 October 2020) failed the test of effectiveness.

In this article we examine the duty of care owed by the Coffs Harbour Council to users of the Coffs Harbour Jetty and why the warning sign was not effective as a risk warning to protect the Council from a breach of its duty of care.

What was the duty of care owed by the Council?

The Coffs Harbour Jetty extends from the shore over a sandy beach then to the harbour. It is a wide wooden jetty with railings on each side. There are two rails – a middle rail 39.5 cm above the base and a top rail 48.0 cm above that, with gaps in between the rails.

The jetty is a heritage item, having been used for cargo handling from 1892 until 1984, when it was closed to the public. It was restored for use as a public walkway and was opened to the public in 1997 as a tourist attraction. It was handed over to the Council in 2002.

On 30 September 2011, the plaintiff, a little boy then aged five, fell through the rail and landed onto hard sand some 4 metres below. He suffered serious injury, including to his brain. He had been walking with his grandparents, who were close by. They had stopped at the rail to look out at the people swimming. As they resumed their walk, they took their eyes off the boy, and that is when he fell through the rail.

The Council owed a duty of care because the jetty was under its care, control and management.

The NSW Court of Appeal (Leeming JA, Basten JA and Macfarlan JA agreeing), identified the duty of care in this case as: to take precautions against the risk of a child falling through the rails onto the hard sand below and suffering harm.

But was the Council in breach of its duty of care, and therefore negligent?

Section 5B of the Civil Liability Act 2002 (NSW) sets out three requirements for negligence:

(1) A person is not negligent in failing to take precautions against a risk of harm unless—

- the risk was foreseeable (that is, it is a risk of which the person knew or ought to have known), and

- the risk was not insignificant, and

- in the circumstances, a reasonable person in the person’s position would have taken those precautions.

The risk of harm was foreseeable and was not insignificant - the Council knew that children had fallen, or nearly fallen on three occasions previously. On one occasion there were serious consequences.

The Court said that a reasonable person in the position of the Council would have made the railing safe by installing additional stands of wire or infill to narrow the gaps in the railing, to prevent children from falling through.

Therefore the Court found that the Council was negligent because all three requirements were satisfied.

In so saying, the Court rejected the Council’s submission that the railing was sufficient because it complied with Australian standards at the time the wharf was restored and reopened in 1997:

“The Council’s submission does not attend to the proposition that what is a reasonable response varies over time, depending on the known history of the site.”

That is, safety measures need to be reviewed and upgraded over time.

Was the warning sign an effective risk warning?

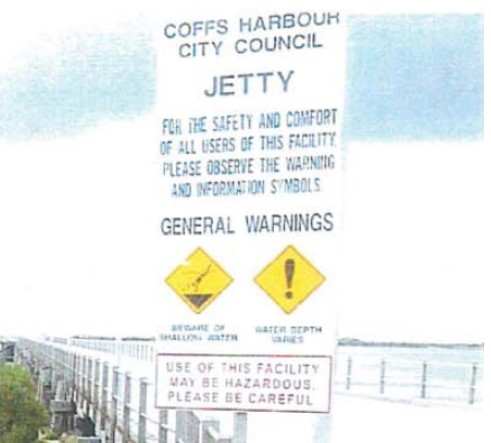

The Council relied upon a sign at the entrance to the jetty. This was the sign:

The “GENERAL WARNINGS” words, and the yellow diamonds (and words below) refer to the dangers of diving into shallow water. At the bottom are the words:

“USE OF THIS FACILITY MAY BE HARZARDOUS. PLEASE BE CAREFUL”

The Court had to decide whether the risk warning was sufficient warning to satisfy s 5M of the Civil Liability Act 2002 (NSW) of the general nature of the particular risk that a child might fall:

5M No duty of care for recreational activity where risk warning

(1) A person (the defendant) does not owe a duty of care to another person who engages in a recreational activity (the plaintiff) to take care in respect of a risk of the activity if the risk was the subject of a risk warning to the plaintiff.

…

(5) A risk warning need not be specific to the particular risk and can be a general warning of risks that include the particular risk concerned (so long as the risk warning warns of the general nature of the particular risk).

The Court found that s 5M did not apply for these reasons:

“Read as a whole, the sign was directed to the risk of diving from the jetty into water whose depth varied with the tide. There is nothing in the warning alerting the reader to a quite different risk, one which is potentially very dangerous for young children, namely, falling from the wharf more than four metres onto hard sand. The risk warning did not warn of the general nature of the particular risk – the risk of a young child falling through the railing onto the hard sand below – which eventuated in this case.” [judgment, paragraph 119]

The Court concluded that the Council could not rely upon the sign as a risk warning under s 5M to avoid a duty of care. As a result, the order against the Council to pay more than $750,000 in damages for the child’s injury stood.