OceanGate will rely heavily upon its liability waiver to avoid liability for claims for compensation arising from the catastrophic implosion of the OceanGate Titan submersible.

After the threshold issues of choice of law and applicable law are dealt with, the legal argument will centre upon whether OceanGate and/or its suppliers can rely upon the liability waiver to avoid liability for negligence (breach of duty of care) or for contractual obligations (to use due skill and care) to provide a safe passage.

In this article we will examine why the liability waiver might or might not be effective to protect OceanGate against negligence and contractual obligations.

The OceanGate Liability Waiver

While OceanGate’s Liability Waiver is not a public document, these extracts have been quoted in the media:

- The waiver repeatedly warns of “the risk of death” when in the company’s submersibles.

- The waiver contains this assumption of risk: “I hereby assume full responsibility for the risk of bodily injury, disability, death, and property damage due to the negligence of any Released Party while in operation”.

- The waiver contains this description of the submersible: “This operation will be conducted inside an experimental submersible vessel that has not been approved or certified by any regulatory body, and may be constructed of materials that have not been widely used in human-occupied submersibles.”

- The waiver contains this risk warning: “When diving below the ocean surface this vessel will be subject to extreme pressure, and any failure of the vessel while I am aboard could cause severe injury or death”.

- The waiver contains this acknowledgement of risk: “I acknowledge that all travel in or around the water on vessels of any type, including submersibles, entails both known and unanticipated risks that could result in physical injury, disability, emotional trauma, death, harm to myself or third parties, or damage to my property …”.

- The waiver contains a choice of law clause that disputes over the waiver will be “governed by the laws of The Bahamas”, where OceanGate Expeditions Ltd is registered. The laws of the Bahamas are based on English common law.

The English common law is presumed to apply, for the purposes of this article.

Also presumed is that the liability waiver was signed by all ‘explorers’, as OceanGate calls them, so that they were aware of it.

What happened to the Titan submersible?

There appears to have been a catastrophic implosion of the submersible at about 9:45 am on Sunday 25 June 2023 (local time), which occurred after 1 hour 45 minutes into the dive. It was found close by the wreck of the RMS Titanic on the seabed of the North Atlantic Ocean. Parts of the 6.7 metre hull have been recovered with damage consistent with a catastrophic implosion caused by extreme water pressure found at the ocean depths where the wreck lies.

The cause or causes of the catastrophe, and who is responsible, might take months or even years to determine.

In analogous situations of aircraft disasters, the pieces of the aircraft are painstakingly assembled and examined. Not only the airline but also a manufacturer or a supplier can be found to have contributed to the disaster. For example, the causes of the Boeing 737 MAX crashes were attributed to aircraft design, maintenance and flight crew actions.

What were the ‘explorers’ promised?

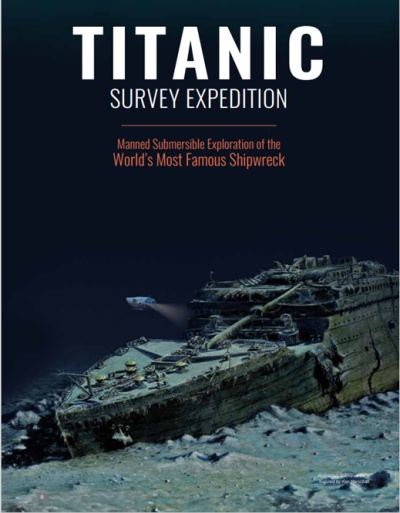

The brochure describes ‘Expedition Objectives’ of the Titanic Survey Expedition as being:

Manned Submersible Exploration of the World’s Most Famous Shipwreck

The Titanic Survey Expedition will conduct an annual scientific and technological survey of the wreck with a mission to: Create a detailed 3D model, … capture data and images, … document the condition of the wreck, … document the marine life inhabiting the wreck site …

“This not a thrill ride for tourists. It is much more”. According to OceanGate.

Yet on the OceanGate website, a different impression is given “Become one of the few to see the Titanic with your own eyes”.

There are no assurances of safety, compliance, certification and the like in the brochure. If this appears to be unusual, the omission was deliberate.

The submersible was the brainchild of Stockton Rush, who co-founded OceanGate. He said: “This technology is what we need to explore the ocean depths” as he launched the Titan publicly in 2018.

The vessel had not been independently certified because OceanGate believed this would “stifle innovation”. Certification was not mandatory because the submersible was operating in international waters.

There were concerns that the carbon fibre used to construct the submersible was untested. That it was the first application of the technology to this kind of submersible vehicle (the nose cone and rear cone were made of titanium joined to a carbon fibre body).

The cost was US$250,000 per person.

Negligence

A carrier has a duty of care to keep passengers safe from harm. As a matter of course, carriers use liability waivers to exclude liability for bodily injury, disability, death, and property loss and damage due to their negligence or their servants or agents.

The question is: how effective are liability waivers when a ship sinks?

The White Star Line issued tickets for the maiden voyage of the Titanic in April 1912, with conditions for transportation on the back of the ticket. The liability waiver condition was:

… the shipowner … shall [not] be liable to any passenger carried under this contract, for loss, damage or delay to the passenger … arising from … perils of the sea … even though the loss, damage or delay may have been caused or contributed to by the shipowner’s servants...

In a test case decided on February 9, 1914, in the Court of Appeal (on appeal from the King’s Bench, in England), Chief Justice Vaughan Williams found that the captain was negligent by continuing to sail full steam ahead, despite at least three warnings of icebergs ahead. The condition of transportation did not protect the White Star Line from negligence because it had not been approved by the British Board of Trade.

Will history repeat?

Since that test case, Courts have regularly upheld liability waivers for negligence. But will a Court uphold a liability waiver if there has been gross negligence?

In the analogous situation of claims for death and injury to passengers on an aircraft, a distinction is made between negligence and gross negligence. An airline’s liability for death or injury on an international flight is limited to a set amount if the negligent acts or omissions which cause death or injury are an accident. But if the negligent acts are reckless, careless, or intentional, that is, grossly negligent, no liability limit applies.

Will the deliberate action of OceanGate in having the submersible vessel constructed with an experimental design which was not in accordance with an industry standard, not having the vessel adequately inspected, tested, certified or classed, as safe for dives to depths of 4,000 metres, amount to gross negligence?

OceanGate will argue that it warned the ‘explorers’ in the liability waiver that the “experimental submersible vessel … has not been approved or certified by any regulatory body and may be constructed of materials that have not been widely used in human-occupied submersibles”. But that warning may not be effective, given the extreme risks and ultrahazardous activities.

The risk disclosures and warnings will be closely examined and strictly interpreted, applying the contra preferentem rule of legal interpretation.

Take “this vessel will be subject to extreme pressure, and any failure of the vessel while I am aboard could cause severe injury or death”. If the cause of the catastrophe is found to be that the carbon fibre failed due to the stress of repeated deep dives, then the warning that injury or death could result from “failure” might be too general to protect OceanGate.

OceanGate will also argue that the expedition was a dangerous activity and that the risk of death or injury was obvious. That there was a voluntary assumption of risk by the ‘explorer’ and the rule of volenti non fit injuria applies. This argument can be sustained only if the ‘explorer’ had full knowledge of the risks they assumed. The question will be whether the dangers were fully disclosed in the liability waiver.

Finally, in this case, there is the issue of informed consent. There were passengers from non-English speaking countries, who may not have been properly informed of the risks.

The contractual obligation to use ‘due skill and care’

At common law, a term is implied into a travel contract that the operator carry out its services with reasonable skill and care.

A leading decision on the contractual obligation is Wong Mee Wan v Kwan Kin Travel Ltd. In that case, a passenger travelling in a speedboat was thrown out of the boat and drowned when the speedboat collided with a fishing junk while crossing a lake. The Privy Council (in London) found that the tour operator who had arranged the speedboat had not taken reasonable care to ensure that the driver of the speedboat was reasonably competent and experienced. No liability waiver was argued in that case.

This decision is relevant because the Judicial Committee of the Privy Council (in London) is the final court of appeal for the Bahamas.

Of course, liability waivers can exclude liability under a contractual obligation to use ‘due skill and care’. Arguments of interpretation and whether the waiver purports to exclude all obligations under the contract are relevant.

Conclusion

It is unsafe to rely upon a liability waiver for an adventurous activity, without taking reasonable precautions against harm.

The activity should be reviewed by a safety expert, and their recommendations be followed.

If safety certification is available, it should be obtained, even if not strictly required.

OceanGate has failed to take reasonable precautions to provide a safe passage. As a consequence, it is unlikely to be able to rely on the liability waiver to avoid liability from claims arising from the loss of the Titan submersible.

Image from OceanGate Expeditions brochure

Image from OceanGate Expeditions brochure