The Trivago online business model

Trivago operates an online search and price comparison site for hotel accommodation. Trivago aggregates room offers – and displays a list of the cheapest room offers for a selected location, stay dates and type of room searched. The list can be filtered by rating, distance, price and accommodation type.

The cheapest room rate is highlighted (the ‘Top Position Offer’).

Bookings are easy to make by clicking on the room offer, which redirects the inquiry to the hotel’s website, where the consumer makes the hotel room booking directly.

Trivago’s revenue is derived from online accommodation booking sites. The hotel (or house or apartment) pays Trivago a “cost per click” (‘CPC’) for each “click” on its room offer, regardless of whether it converts into a booking. Trivago does not charge a fee to consumers for use of its website.

The Trivago business model was very successful. In the 13 month period from 1 December 2016 to 3 January 2018, there were 217 million site visits to the Initial Search Results Page (where the Top Position Offer was displayed) on Trivago’s Australian website.

But did its success come fairly or was it from misleading consumers? The statistics show a bias towards the Top Position Offer. On 20 million occasions, the Top Position Offer was clicked, but on only 4.7 million occasions was the More Deals slide-out clicked.

The Australian Competition and Consumer Commission prosecuted Trivago for contraventions of the Australian Consumer Law not only for reasons of consumer protection but also for unfair competition.

As ACCC Chairman Rod Sims explained in a media release:

“We brought this case because we were concerned that consumers were being misled by Trivago’s claims that their site was getting the best deal for consumers, when in fact they were shown the deals that benefited Trivago.”

“Trivago’s conduct meant that consumers may have paid more for a room at a hotel than they should have, and hotels lost business from direct bookings despite offering a cheaper prices,” Mr Sims said.

What made the Trivago website misleading and deceptive?

In its decision Trivago N.V. v Australian Competition and Consumer Commission [2020] FCAFC 185 (4 November 2020), the Full Court of the Federal Court of Australia (Middleton, McKerracher and Jackson JJ) identified four representations made on the Trivago website and in its television advertising which were misleading or deceptive conduct or were false and misleading representations contrary to: sections 18 (misleading or deceptive conduct), 29(1)(i) (false or misleading representations with respect to the price of services) and 34 (misleading conduct as to characteristics of services) of the Australian Consumer Law.

They were:

1. Cheapest Price Representation

Trivago made this ‘best price’ representation in its television advertising which it used to direct Australian consumers to its website.

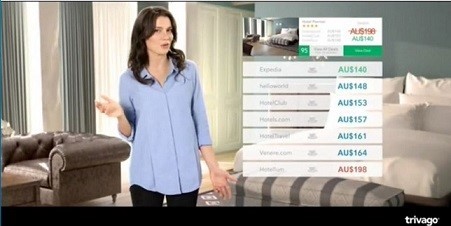

The presenter (pictured below) stated: “Trivago does the work for you and instantly compares the prices of over 600,000 hotels from over 200 different websites … Trivago shows you all the different prices for the exact same room … You can be sure that you find your ideal hotel for the best price … Hotel? Trivago”

The “best price” representation also appeared on the website. On the Landing Page (where the location, stay dates and room type are selected), Trivago used these slogans: “Find your ideal hotel for the best price” and “Find your ideal hotel and compare prices from different websites”.

The Court found that the “best price” representations were misleading or deceptive under the Australian Consumer Law.

The Court found that ordinary and reasonable members of the public were misled because they chose the Top Position Offer over alternative cheaper offers for the same room in 66.8% of cases, even though in only 33.2% of listings was the Top Position Offer the cheapest offer.

The Court found that the main reason why a hotel room was displayed as a Top Position Offer was because Trivago’s Algorithm placed a significant weighting on the value of an online booking site’s cost per click. It favoured hotels which had paid higher fees per click.

Trivago discontinued the television advertising and removed the ‘best price’ slogans from its website in the course of the legal proceedings.

2. Strike-Through Price / Red Price Representation

This is an example of the Top Position Offer for an apartment in Canberra. Note the three other offers and “More Deals” in grey text in the box to the left:

Immediately above the green Top Position Offer on the website, is another offer - a higher price in red with a strike-through. In later versions, the price appeared in red with no strike-through.

The juxtaposition of the two price offers conveyed the impression that apart from price, the offers were “like-for-like”.

The Court found that the price offers were not comparable because the higher price was for a superior room or room with superior amenity in the same hotel. The representation was therefore misleading or deceptive under the Australian Consumer Law.

Trivago argued that it had an explanation which was sufficient to dispel the misleading impression. The explanation was contained in display text which appeared if the consumer hovered their mouse cursor over the red strike-through price. The text included: “the cheapest deal from the most expensive booking site with offers for this hotel”.

The Court rejected Trivago’s argument for two reasons. First, there was no “conventional visual cue, such as a clear asterisk or footnote” to indicate the existence of the qualification. Second, the “content of the hover-over text was confusing”.

Trivago discontinued the strike-through price / red price in the course of the legal proceedings.

3. Top Position Representation

Apart from its position, the formatting of the Top Position Offer on the Landing Page gave the impression that it was either the cheapest available offer or had some other characteristic which made it more attractive than any other offer.

The formatting was that the offer had a green colour (suggesting positive associations), it was in a relatively large font, had white space around it and had a large green “View Deal” button below it (see image above).

The Court found that the impression given by the formatting was misleading because the Top Position Offer was not the cheapest available offer (or was otherwise attractive). Trivago gave the Top Position Offer to the hotel with the highest ‘pay per click’ bid on most occasions.

Trivago relied upon the disclosure in the text displayed when the mouse hovered over the Our Recommendations button. The text was:

“In determining the price to display in the leading position of our search results, we consider a variety of factors, including price, the likelihood that you will find your ideal hotel, your ability to complete a booking after you click on a search result and the level of compensation provided by the booking sites we cover. In order to make more information available on pricing options to our users, additional prices are listed in the “More deals” slide-out.”

The Court rejected this argument because it was not obvious to consumers that the Top Position Offer was qualified, and the information in the hover-over was too “opaque”.

4. Additional conduct allegations

Taken together, the Cheapest Price Representation, the Strike-Through Price Representation and the Top Price Representation led “consumers to believe that the Trivago website provided an impartial, objective and transparent price comparison which would enable them to quickly and easily identify the cheapest available offer for a particular (or the exact same) room at a particular hotel”.

Having found that the three representations were misleading, the Court found the additional conduct allegations were also misleading in contravention of the Australian Consumer Law.

Conclusions

Trivago has been modifying its website since it first became aware of the ACCC’s concerns. It has removed the obvious contraventions: the strike-though price, the words “best price” and has made the content more transparent. It has ceased television advertising.

These modifications will be taken into account when the case returns to the primary judge to make declarations, injunctions and order penalties and costs against Trivago.

But will these modifications be enough? Will the Court make declarations and injunctions so wide as to render the Trivago online business model no longer viable? Only time will tell.