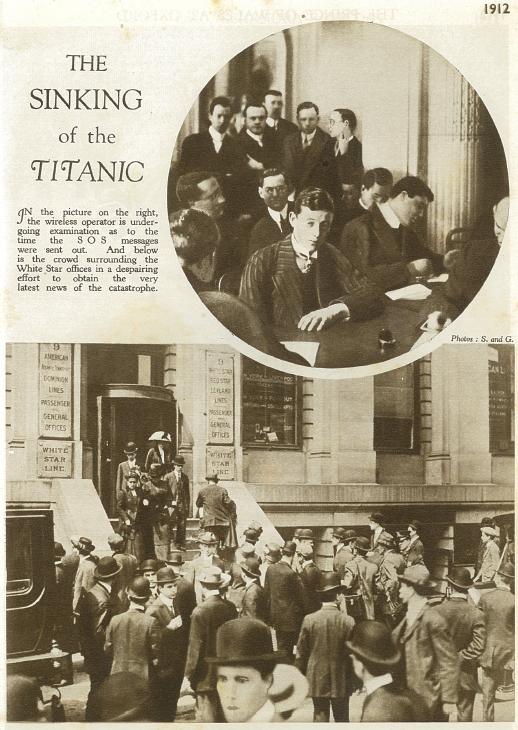

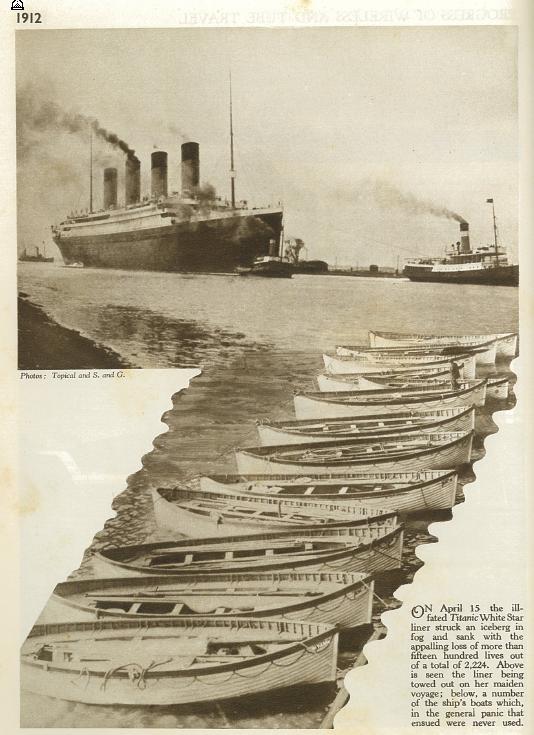

The world was in shock when the ‘unsinkable’ Titanic sank on her maiden and final voyage in the early hours of 15 April 1912.

What went wrong, and what could have been done differently, was the subject of a US Senate Inquiry instigated by Senator William Alden Smith and a British Inquiry presided over by Lord Mersey, the Wreck Commissioner. It was also the subject of many private law suits.

I was very fortunate to be privy to a legal presentation on The Sinking of R.M.S. Titanic by Joseph A. Kilbourn from the New York law firm of Bigham Englar Jones & Houston, who were the lawyers who acted for the cargo insurers handling claims from the loss of the R.M.S. Titanic. The presentation was drawn from the original legal files for the Titanic law suits which are kept securely in its safe.

These are the six lessons the world has learned:

Lesson One – The bulkheads should be watertight

Bulkheads on a ship are like canisters – they are lined up inside the hull, side by side, so that if water enters from a breach of the hull, the bulkhead fills up with water, not the whole hull. In this way, the ship maintains its buoyancy.

The Titanic had fifteen bulkheads, the tops of which extended up above the waterline. The bulkheads were built to comply with current maritime standards. The problem was that the standards did not require the bulkheads to be capped. It was like a canister without a lid.

After the collision with the iceberg, five of the bulkheads on the starboard bow gradually filled with water. As they filled, the ship listed and because the bulkheads were not capped. The water slopped over the tops into the other bulkheads. Soon the other bulkheads started to fill with water and the ship sank ever more rapidly.

The Inquiries found that the main reason that the Titanic sank was the fact that the bulkheads were not capped, and therefore not watertight.

Lesson Two – The double hull could have been better designed

The Titanic had been designed with an outer hull, and with an inner hull between 63 and 75 inches inside, to provide extra protection if the outer hull were breached, such as by grounding. The fact that the double hull extended up the sides of the hull was the main reason why the Titanic was considered by its owner to be ‘unsinkable’. Or as the owner put it – the whole ship was a lifeboat.

The poor design lay in the fact that around the turbine and engines, the inner hull had not been extended above the waterline, to where it had been extended elsewhere on the hull.

Once the ship started listing, and water filled the gap between the double hull to the waterline, slopping over the inner hull near the machinery space, where the pumps were unable to contain the flooding.

Lesson Three – Not enough lifeboats

The Titanic was designed to carry 32 lifeboats, which could have carried 2,160 passengers. There were 2,201 passengers on board, and so 32 lifeboats would have almost been enough.

A lifeboat is attached to a davit, which consists of two steel arms with ropes and pulleys to allow the lifeboat to be lowered into the water. The davits on Titanic were Wehlin double-acting davits - designed for two lifeboats per davit.

The owner of the Titanic, the White Star Line, chose to fit one lifeboat per davit instead of two lifeboats per davit. Therefore it carried 16 lifeboats, one for each of the 16 davits, plus four collapsible lifeboats, which meant that there was capacity for 1,178 passengers. This complied with current maritime standards. The standards were based on tonnage, not numbers of passengers!

At the Inquiries, the question was asked – Why did you not fit two lifeboats per davit? The official answer was that maritime standards did not require it. But the unofficial answer was that the extra lifeboats were not fitted because they would have cluttered up the Boat deck – was this to provide more room for the deckchairs on the Titanic to be re-arranged perhaps?

Lesson Four – Iceberg warnings should not be ignored

Although the Titanic took the winter route (or southern track) across the Atlantic Ocean because it was freer of any ice, it was still a route where icebergs had been sighted in April. During the day of April 14, four separate ice warnings were received from other ships warning of icebergs within 5 miles of the track the Titanic was taking. Captain Edward Smith heeded these warnings and steered a more southerly course.

The last of these ice warnings was from the Californian which was about 5 miles away at 10:00 pm, and was given about an hour and a half before the accident occurred – ‘We are stopped and surrounded by ice.’

This ice warning was infamously ignored by the radio operator - it was not passed on to the bridge. The radio operator was too busy sending personal messages for the first class passengers – his reply was ‘Shut up. I’m too busy.’

Lesson Five – Full Speed can be dangerous

The official policy of the White Star Line was that in clear weather, ships should be navigated at full speed, day and night. This policy of sailing ‘at a fair clip’ could have originated from the days when the White Star Line was sailing clippers to Australia in the 1860s.

In any event, J Bruce Ismay, the managing director of the White Star Line was on board, and he wanted to show that his newest and most luxurious ship could cross the Atlantic fast! His instructions to Captain Edward Smith were - in clear weather, whether it be day or whether it be night, there should be no reduction or need be no reduction in the speed, although the master of the ship knows that he is in the ice region.

The night of 14 April 1912 was clear, the seas were calm, the stars were out, but there was no moon. The Titanic was proceeding at full speed ahead at 22 knots, its maximum speed. At 11:40 pm one of the lookouts in the crow’s nest struck three blows on the gong, an accepted warning of danger ahead. Despite turning the wheel ‘hard-a-starboard’ and telegraphing the engine room ‘Stop. Full speed astern.’ the Titanic could not avoid the iceberg less than a minute later.

The British Inquiry (somewhat unbelievably) exonerated Captain Edward Smith (who admittedly had gone down with his ship) but added - ‘What was a mistake in the case of the ‘Titanic’ would without doubt be negligence in any similar case in the future.’

Lesson Six – Lifeboat drills are important

The first and second class passengers had easy access to the Boat deck by staircases and elevators. The third class passengers had to take a more difficult route to reach the Boat deck – they could take staircases to the C deck, and then reach the Boat deck by ladders on the port and starboard sides, or pass through emergency doors to a passageway and then take stairs to the Boat deck.

There were no lifeboat drills held on the Titanic.

Shortly after midnight, Mr Thomas Andrews, the Managing Director of Harland & Wolff, the builders of the Titanic reported to Captain Smith that it was a mathematical certainty that the ship would founder. The stewards were ordered to awaken each passenger and to tell them to come to the Boat deck dressed in a life jacket. Under order of ‘women and children first’ the lifeboats began to be filled and then lowered from 12:45 am until 2:05, by which time all 16 lifeboats and 2 of the 4 collapsible boats had been lowered. The lifeboats were just over half filled when launched. Out of 1,178 places available in the lifeboats only 706 were filled.

The lack of a lifeboat drill therefore had fatal consequences – there was a lack of familiarity with emergency procedures and with the access routes to the Boat deck, accentuated by the fact that it has been estimated that 500 of the passengers may not have been English speaking.

The Titanic disaster shocked the world into making passenger ships safer. All of the lessons were heeded. Two years afterwards, in 1914 the International Convention for the Safety of Life at Sea was agreed.

Today, countries around the world have laws for safety on shipping, and international conventions extend these laws to sailing on the high seas.